Later models of the Trimphone were made with pushbutton dialling

(both pulse and tone versions).

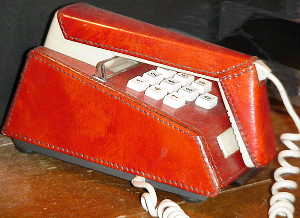

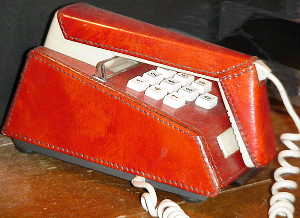

The final design was “enhanced” by having a leather covering stuck on.

This slightly naff leather-clad model was called the Deltaphone.

Later models of the Trimphone were made with pushbutton dialling

(both pulse and tone versions).

The final design was “enhanced” by having a leather covering stuck on.

This slightly naff leather-clad model was called the Deltaphone.

| Time Warp Telephones |

Here's a selection of British telephones from that in-between stage of development when Bakelite was obsolete but cell-phones were still in the future. Don't forget that the telephone system in the UK was a monopoly, run by the Post Office (GPO) until the 1980s. Ordinary customers (“subscribers”) were not allowed to plug in their own phones, nor were they allowed to connect modems.

Perhaps the best-known “luxury” phone was the Trimphone. It was introduced in 1969, and made by STC. Of course, you couldn't buy one, you had to rent it from the GPO. It had an electronic ringer, a glow-in-the-dark dial and was available in a variety of colours. In the photo, the different models are (left to right) pushbutton pulse-dialler, pushbutton Deltaphone, red pushbutton pulse-dialler, blue rotary dial and pushbutton tone-dialler.

Later models of the Trimphone were made with pushbutton dialling

(both pulse and tone versions).

The final design was “enhanced” by having a leather covering stuck on.

This slightly naff leather-clad model was called the Deltaphone.

Later models of the Trimphone were made with pushbutton dialling

(both pulse and tone versions).

The final design was “enhanced” by having a leather covering stuck on.

This slightly naff leather-clad model was called the Deltaphone.

From Sweden came the Ericofon, made by

Ericsson.

Yes, the same company that's now well-known for their cell phones,

DECT phones and mobile internet access.

I have examples of both the original Ericofon 600 and

the newer, push-button version, the 700.

The Ericofon 600 was designed in 1954, while the 700 was designed

in 1976.

Note that even though the user can dial quickly on the

push-button version,

the phone stores the digits and slowly pulse-dials them onto the line.

All British push-button phones of this era had to pulse-dial,

and were much more complicated electronically as a result than

tone-dialling phones.

From Sweden came the Ericofon, made by

Ericsson.

Yes, the same company that's now well-known for their cell phones,

DECT phones and mobile internet access.

I have examples of both the original Ericofon 600 and

the newer, push-button version, the 700.

The Ericofon 600 was designed in 1954, while the 700 was designed

in 1976.

Note that even though the user can dial quickly on the

push-button version,

the phone stores the digits and slowly pulse-dials them onto the line.

All British push-button phones of this era had to pulse-dial,

and were much more complicated electronically as a result than

tone-dialling phones.

The 700 model is fitted with a 5-pole jack plug, which the GPO used to connect non-standard phones (the usual connection was permanent wiring to a junction box). The photo below shows the bottom of the phone, where the dial is located. The red rectangular projections are the tips of the switch that “hangs up” the phone when it's not in use.

This phone is popular enough to have its own Web site,

Ericofon.com.

Telephone call charging in the days of electromechanical exchanges

was a tricky business.

Calls were metered in “units” according to duration, distance

and time of day.

Then, subscribers were billed by charging for units at a certain rate.

A gadget called the Monitel was invented in the 1970s to show a

running display of how much, in pence, a call was costing.

Of course, it had to be programmed with the tariff, that is, how

many seconds to a unit (for each of the three distance bands) and how

much each unit cost in pence.

For this, the Monitel had a crude punched-card reader built-in.

Telephone call charging in the days of electromechanical exchanges

was a tricky business.

Calls were metered in “units” according to duration, distance

and time of day.

Then, subscribers were billed by charging for units at a certain rate.

A gadget called the Monitel was invented in the 1970s to show a

running display of how much, in pence, a call was costing.

Of course, it had to be programmed with the tariff, that is, how

many seconds to a unit (for each of the three distance bands) and how

much each unit cost in pence.

For this, the Monitel had a crude punched-card reader built-in.

The other problem was the GPO monopoly, which prevented the Monitel from connecting in any way with the phone or the line. So, the user first had to find out which charging rate applied to the call (by distance, “Local”, “a” or “b” rate) and then start the counter when the call was connected. The Monitel knew the time of day, and day of the week, and then used the tariff information to display the cost of the call on a green fluorescent display.

The whole device was shaped to fit exactly underneath a standard GPO

phone and was moulded in the same colours as the GPO offered.

My example is cream in colour.

This phone was built for use in places where there's a risk of an

explosion being triggered by a tiny spark.

This kind of explosive atmosphere can be found underground in mines,

and in industrial locations such as chemical plants and oil

refineries.

Normal electro-mechanical telephone dials generate these tiny sparks at

the electrical contacts, whenever the dial is used.

The same thing happens at the hook switch contacts whenever the

handset is lifted or replaced.

To make the phone safe in a potentially explosive atmosphere,

the entire casing is sealed and air-tight.

It's also extremely rugged,

being made almost entirely of thick metal castings.

The compartment at the bottom, also air-tight, houses just the terminals

that connect the phone to the line.

The bolts that hold the covers on have unusual triangular heads, perhaps

to prevent a user with a normal spanner from tampering with it.

This phone was built for use in places where there's a risk of an

explosion being triggered by a tiny spark.

This kind of explosive atmosphere can be found underground in mines,

and in industrial locations such as chemical plants and oil

refineries.

Normal electro-mechanical telephone dials generate these tiny sparks at

the electrical contacts, whenever the dial is used.

The same thing happens at the hook switch contacts whenever the

handset is lifted or replaced.

To make the phone safe in a potentially explosive atmosphere,

the entire casing is sealed and air-tight.

It's also extremely rugged,

being made almost entirely of thick metal castings.

The compartment at the bottom, also air-tight, houses just the terminals

that connect the phone to the line.

The bolts that hold the covers on have unusual triangular heads, perhaps

to prevent a user with a normal spanner from tampering with it.

Return to the Old Sad Things page

Return to John Honniball's home page

Copyright © 1998-2003 by John Honniball. All rights reserved.